Gift, Ground, & Gratitude: An Ecology of Power

“The ‘Rights of Mother Earth’ is a call to leave the dominant anthropocentric paradigm and to imagine a new Earth Society.” – Vishwas Satgar

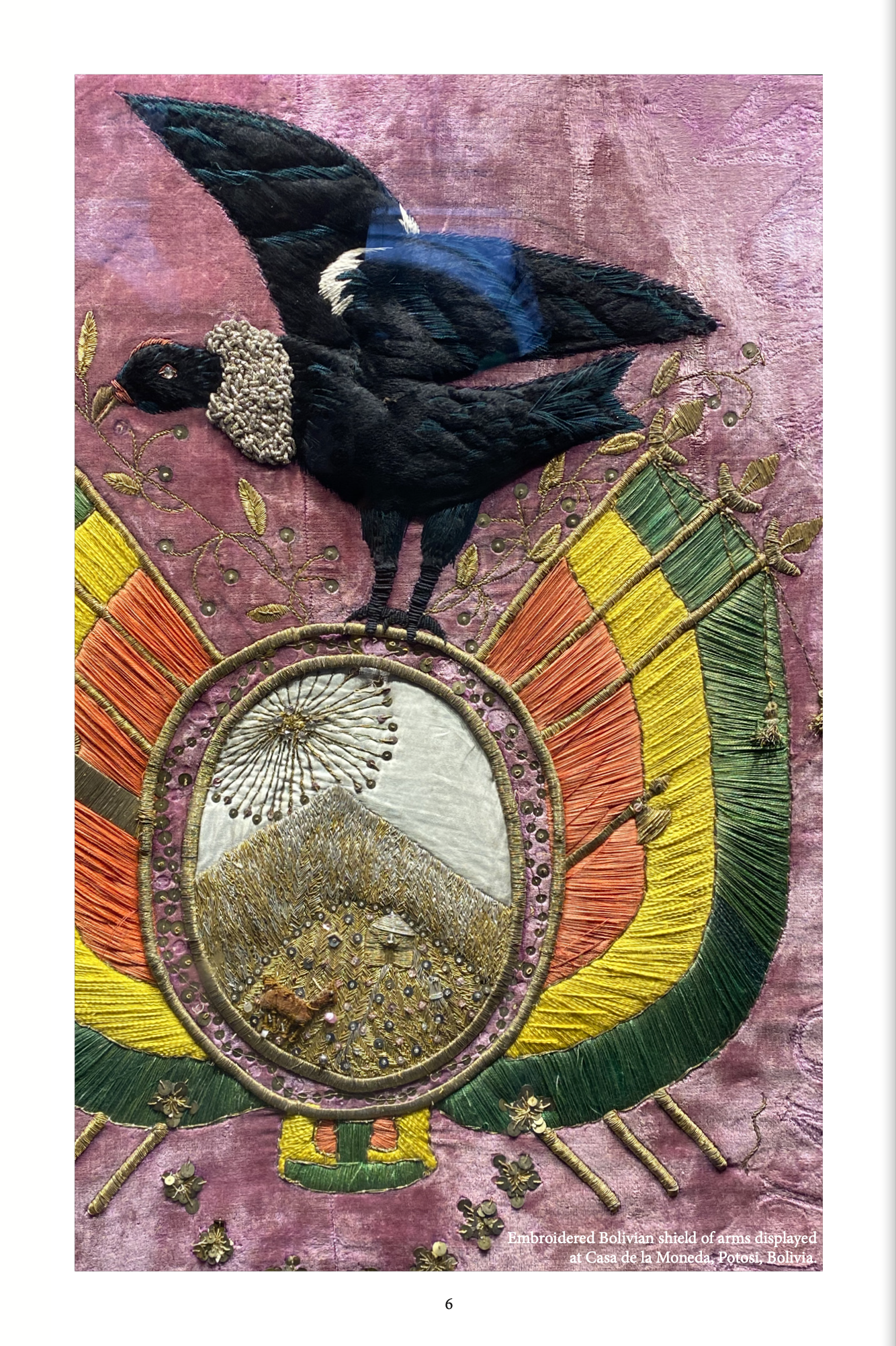

Bolivia’s most sacred piece of nature is the Cerro Rico, a mountain adjacent to the ancient mining town of Potosi. It continues to be honored on the country’s flag, inside of the shield of arms. The native people of the land held values, tales, and even mythology tied to the Cerro Rico, including an appreciation for nature that is admirable in today’s anthropocentric society where material objects are valued more than mother nature, or pachamama.

Potosi’s namesake itself comes from a meaning thunder, burst, and explosion. It is a derivation from the “Potosji,” the name the Indians changed it to from Cerro after a moment of terror where the mountain screamed to them in Quechua; “this is not for you; God is keepin ghtese riches for those who come from afar.” in reference to the silver contained inside of the mountain (Galeano, 21). This legend has been carried within the communities of Potosi for centuries, with the ultimate fate we know now to have alluded to the 16th century Spanish acquicision of the lands, followed by the beginning of a long history of exploitation of natural resources; gold and silver.

god of undergound

Pachamama

The Aymara people and the Inca people, the original inhabitants of the region we know know as the highland of Bolivia, chersished the Cerro Rico as a ‘huaca,’ or sanctuary. So much so that they attempted to keep it hidden from the spanish conquerers when they arrived. The Aymara’s named it ‘Apu,’ also dedicating it to their ‘‘Apu,’ god of the underworld (Gisbert, 1). Their devotion extended to consultation of their doubts with the demon of the mountain, to which they received an answer, in exchange for sacrifices made to them. When the Incas arrived, they similarly dedicated it to their gods, but this time it was in the name of the Sun, and of Pachacamac, their representation of all the gods and also the start of all life in the universe.

The Spanish arrival to the Aztec, Mayan, and Inca land detoned a new ownership of the Cerro Rico. Under their rule, the Cerro Rico became identified with the Virgin Mary, giving her the name ‘Nuestra Señora del Cerro.’ Interpreting the Virgin Mary as the mother of all things, and most of all of Christ, the analogy applies to the mountain in the recognitin of the precious shimmering stone as Christ, thus the mountain birthing preciousness. ‘Nuestra Señora del Cerro,’ represented in paintings where the mountain and Virgin are depicted as one. Gisbert argues that the importance behind the viceroyalty identifying the mountain with one Virgin implicates the elimination of multiple gods, or representation of multiple worship.

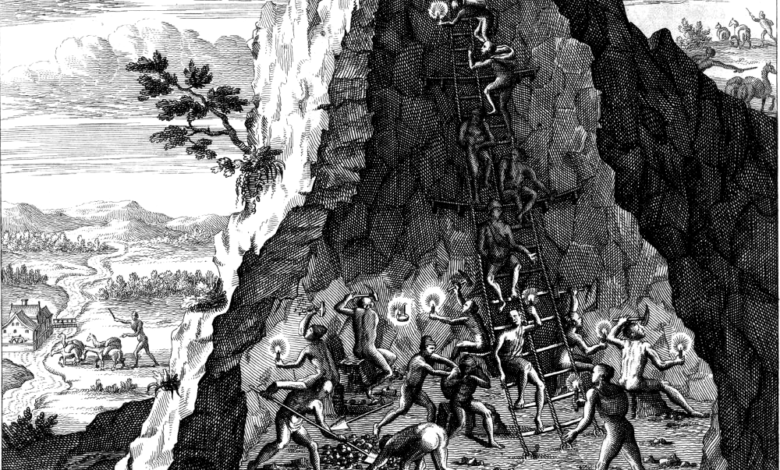

Today, the miners believe in a derivation of the diablada dance. They honor “El Tio,” the Spanish word for ‘uncle’ that they use to refer to the devil god inside of the mines that owns the mountain. The miners will traditionally bring sacrificial offerings, such as their alcohol, cigarettes, llama blood, and sacred coca, to the Tio in hopes that he will grant them good health and fortunes as they head into the mines – mines that await them with suffocating hot and dense air, with high altitude pressure, and darkness. The Tio stands at the entrace tunnels of the mines in observance that the mines are only successfully accessed by humans that carry values of effort, sacrifice, and human lives (Fernandez Juarez, 25).

Class Themes

gift • gratitude • ritual • ceremony • appreciation • nature•

gift • gratitude • ritual • ceremony • appreciation • nature•

product transparencycommunication to publicappreciation for nature

preserving indigenous values

framework

in booklet

REFERENCES

“El Documental La Mina Del Diablo.” YouTube, Rtve, https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=OkzFHaggNBo. Accessed Oct. 2022.

Fernandez Juarez, Gerardo. “El Culto Al ‘Tío’ En Las Minas Bolivianas .” Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, vol. 597, March 2000, pp. 25–31.

Formafantasma, director. Taxonomy, 01:05:58" - Formafantasma, Ore Streams - 2018. Vimeo, 10 Dec. 2022, https://vimeo.com/317456342. Accessed Dec. 2022.

Galeano, E., Belfrage, C., & Allende, I. (2010). Open veins of Latin America: Five centuries of the pillage of a continent. Three Essays Collective.

Gisbert, Teresa. “El Cerro De Potosi y El Dios Pachacamac.” 2010, https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-73562010000100028.

Harper, Jake. “Photos: Dust and Danger for Adults - and Kids - in Bolivia’s Mines.” NPR, NPR, 17 Nov. 2018, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/11/17/665863261/photos-dust-and-danger-for-adults-and-kids-in-bolivias-mines.

Nash, J. (1972). The Devil in Boliva’s Nationalized Tin Mines. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40401638. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

Mesa Gisbert, Carlos Diego. Historia De Bolivia: Las Cifras Del Pais, Historia, Sociedad, Demografia y Economia. 7th ed., Editorial Gisbert, 2012.

Satgar, Vishwas. The Climate Crisis South African and Global Democratic Eco-Socialist Alternatives. Wits University Press, 2018.

Sheller, M. (2014). Aluminum dreams: The making of light modernity. The MIT Press.